The season of deciduous trees has come, making November a lonely month. For Koreans, November is a month of heartaches, with the anniversary of the Student Independence Movement and Patriotic Martyr’s Day. These anniversaries commemorate Korean independence activists during the Japanese colonial period in the 1900s. As there are various anniversaries related to the independence movements, the Sungkyun Times (SKT) watched the movie, A Resistance, a story about the last of one student in prison who fought for the sovereignty of Korea during the Japanese colonial period.

A Resistance

The Setting of A Resistance

The Japanese colonial period refers to the time when Korea was under Japanese rule from August 29th, 1910 to August 15th, 1945. For 35 years, especially in the 1910s, Koreans had to suffer from impoverishment and suppression of freedom. With their land investigation business, Japan extorted the land of Korea’s royal family, peasants, and government and sold it to Japanese immigrants at a cheap price. Also, Japan limited the freedom of media, publication, and assembly in Korea. Amid escalating complaints, in January 1919, suspicion was widespread about Gojong, the Korean empire’s emperor, having been poisoned by Lee Wang-young who was commanded by Japan, and this resulted in the enhancement of anti- Japanese sentiments among Koreans. In February, urged by these resentments, the 2.8 Declaration of Independence was announced in Tokyo, Japan. Based on this declaration, on March 1st, the day of Gojong’s funeral, about 1.66 million Koreans participated in independence movements throughout the entire country. The purpose of the movement was to proclaim Korea’s independence against the unjustifiable and repressive treatment of colonial occupation under the military rule of Japan. Yu Gwan-sun, a student of Ewha Womans University, went to Cheonan City to lead the independence movements.

Plot of A Resistance (*Spoiler Alert*)

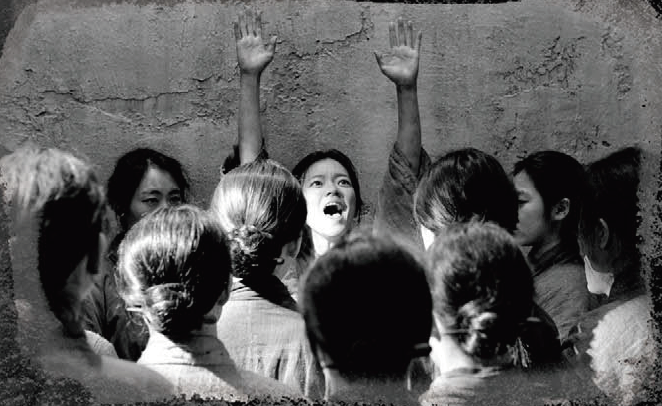

The movie begins with a black-and-white scene with the police detective taking Yu Gwan-sun’s police photograph who was arrested and taken to the Seodaemun Prison under the charges of illegal protest, breach of public order, and contempt of court. Yu was assigned prisoner number three-seven-one and was sent to the 8th room. To avoid their legs from swelling by standing all day long, Yu and the other prisoners walked around the room, singing the Korean folk song Arirang, which energized each other. Despite the warder’s orders to stay quiet, the tunes of Arirang resonated throughout the whole prison. This event planted the impression in prisoners’ minds that light can leak through the cracks in the dark, thick prison walls. Eventually, Yu, who led everyone to sing Arirang, was tortured and taken away to solitary confinement, where she could neither sit nor drink a glass of water, for a week. On March 1st, 1920, the 1st anniversary of the independence movement, with Yu and 8th room prisoners at the head, the independence movement spread again throughout the entire Seodaemun Prison, as well as outside the prison. Forced into solitary confinement and repeated torture due to continuing independence movements, Yu slowly died due to bladder and uterine rupture. When Yu was asked why she continues pursuing the independence movements, she answered, “If not me, then who?” After this conversation, she breathes her last breath in prison, and colors are introduced to the black-and-white film. The movie ends with the words, “Japanese prison officials hid Yu Gwan-sun’s body in an oil crate to burn it. Fortunately, due to the demands of Ewha Womans University, her body was buried at the cemetery in Itaewon. In 1936, however, during the process of airfield construction by Japan, her body ended up lost.”

Charming Points of A Resistance

Black-and-white Film

With its unique calming mood, black-and-white images usually express that the scene is from a long time ago, representing retrospective scenes in movies., In A Resistance, however, scenes are expressed in color only when Yu Gwan-sun is enjoying her freedom, including the scenes that express the time before Yu is sent to prison and after her death. In most of the scenes Yu’s freedom was taken away from her, so almost entire film was expressed in black-and-white, which made this movie special compared to others. Using black-and-white images in the movie also helped to minimize the sadistic and stimulating images that color images could cause when representing Yu Gwan-sun being tortured and assaulted. Also, it maximized the dark society of the time by highlighting the facial expressions and emotions of the characters which caused viewers to breathe and feel the pain and pressure that independence activists had suffered.

Thorough Historical Research

The characters, backgrounds, and props in the movies were all excellently ascertained through the historical research. First of all, actual independence activists of the past, such as Kwon Ae-ra and Kim Hyang-hwa appeared as two of Yu’s fellow inmates. The actual pictures of all the characters, even the minor characters, were all placed in the ending credits. Also, life in Seodaemun Prison was well represented. The prison did not have any medical facilities or a toilet near the rooms, and more than 30 prisoners were confined to a room less than 10m2 wide, wearing the same prison uniform all year without any underwear. The small details that melted into the movie enhanced the audience’s immersion and made the viewers feel like they had a lump in their throats.

"Koreans speak Korean even if they know Japanese."

This line is from Yu Gwan-sun admonishing the Korean police who is threatening prisoners to speak Japanese in an attempt to find out who defied the warder. By saying this, Yu knew that she would be punished. She did not stop, however, because she was confident and proud of speaking Korean. This line shows Yu’s patriotism and her love for Korea.