2024 is the 160th anniversary of the migration of Koryo-saram. Koryo-saram are ethnic Koreans who are descendants of the Korean people who arrived in the Russian Far East in 1863. They were deported to Central Asia in 1937. After years of hardships surviving in foreign lands, many became confused and disillusioned, even questioning their Korean roots. Remembering their distress, the Sungkyun Times (SKT) will delve into their history, discussing how they could flourish as an integral part of Korean heritage.

Koryo-Saram, Who Are They?

-The Tragedy of Forced Migration

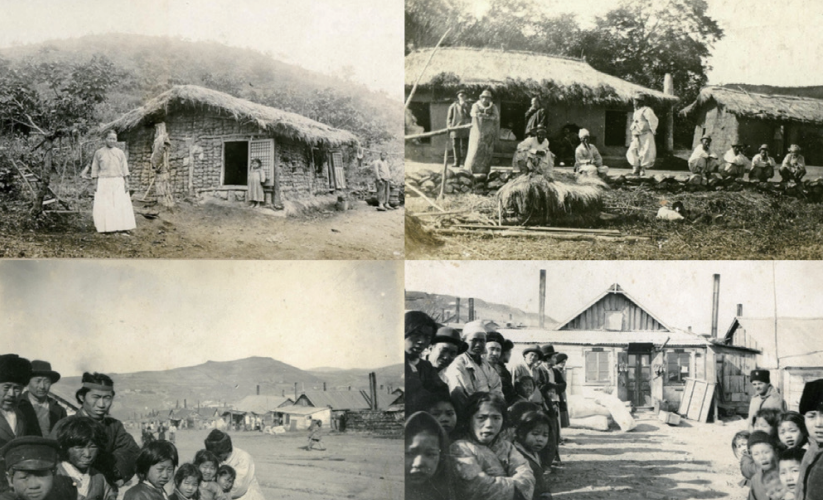

Koryo-saram refers to an overseas Korean who uses Russian as their mother tongue and mainly resides in Russia and other former Soviet republics. There exists a sorrowful backdrop to why these people had to live so far from home. Starting in the 1860s, some Koreans fled from the peninsula to the Primorsky Territory in the Russian Far East due to social turmoil and famine. The population swelled rapidly, and during the Japanese colonial rule, the region served as the base of resistance groups who fought for Korean independence. However, the government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) schemed a relocation strategy towards the Koreans in Primorsky Krai due to rumors of Japanese spy infiltration and concerns that Koreans might assist them. Consequently, intending to develop uncultivated areas, the USSR distributed Koreans across Central Asia. In September 1937, about 170,000 Koreans were loaded onto freight trains and transported across an area of approximately 6,400 km. The train had no toilets or windows, and the poor conditions claimed more than 30,000 lives. After being forcibly cast into the unfamiliar terrain, the people had to battle cold and disease, surviving through an era of anguish until the USSR dissolved in 1991.

-Where Are They Now?

The Koryo-saram had to settle in a foreign land, building houses, cultivating desolate land, and establishing schools. Those who endured all the pain now reside in Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and more. These people have lived in Russian and Central Asian countries for decades, adapting to their structures and coexisting with other ethnic groups. As the international situation improved, the Koryo-saram successfully adopted the doctrines and cultures of respective countries of residence, later playing significant roles in society in different fields such as politics, economy, and medicine. This kind of lifestyle also greatly influenced the perception of their identities. Heo Kristina, a Koryo-saram from Russia told the SKT, “While maintaining an interest in Korea, we normally live more assimilated to the local culture and language,” explaining her self-identification as a Koryo-saram rather than either Korean or Russian. In light of these circumstances, the Overseas Koreans Agency (OKA) conducts homecoming summer camps every year for overseas students to visit their home country and experience Korean culture and history in person. As such, different projects to foster interaction have proceeded over the years to ensure that overseas Koreans reflect on their roots and stay connected.

Ongoing Challenges

-Living in the Land of Strangers

Even after overcoming all hardships, the Koryo-saram still carry the wounds of their past. First, the sorrow and trauma of forced migration were not sufficiently lamented. At the time of the USSR, the Stalinist regime strictly censored unfavorable publications, for which records about the deportation were prohibited. It was only when the USSR was dissolved that memoirs about the incident began to appear. In 1993, the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation issued a decree on the Rehabilitation of Soviet Koreans, anticipating compensation for the deportation. However, as this burden was shifted to the independent individual republics, no practical recompense was realized. Moreover, the history of forced migration has now become a distant tale. The literary critic Choi Jin-seok expressed concerns on the 2018 Diverse Asia webzine, “The term Koryo-saram is now simply used to refer to Russian-speaking overseas Koreans, and the tragedy of forced migration is no longer a pain that resonates with the younger generation.” Furthermore, the latter generation struggles to maintain their ethnic identity. According to a survey conducted in 2017 by the National Youth Policy Institute, teenagers who had attended Korean classes lacked long-term engagement, which led to low identity reinforcement. In other words, despite their interest in Korean culture, it is unlikely to result in concrete actions.

-Living the Life of a Stranger

According to the Ministry of Justice, the number of Koryo-saram residing in Korea surpassed 100,000 in 2023. As much as those living abroad, those returning to South Korea for better prospects also encounter adversities. In fact, the most critical barrier they face is the language barrier. As stated by a Koryo-saram Support Center, survey findings on 306 Koryo-saram living in Ansan City revealed that 70% had a beginner level of Korean proficiency. They face constraints, such as being unable to keep up with classes at school and communicating at work. Teenagers who enter school without learning Korean may even abandon their academic tracks. For adults, the Koryoin Assistance Center offers Korean night classes and mentoring programs tailored to their schedules, although more is needed given the rapid increase in their population. In addition, visa qualification is another barrier to their establishment in South Korea. Typically, the Koryo-saram receive an Overseas Korean Visa (F-4), which allows unrestrained stay if they renew it regularly. However, those from countries other than Russia are given a Visit Visa (H-2) if they fail to present the required academic background or certificates because of the lack of physical evidence. Despite this bitter reality, the government’s efforts towards social integration are exiguous.

The Next Destination

-Commemorating the Past

The Korean government must reevaluate the lives of Koryo-saram as part of national history to mourn their pain. To draw public interest in their historical backgrounds and current circumstances, producing digital content such as documentaries or films about their story would be beneficial. Once created, it would serve as a meaningful material conveying a message of cultural exchange, as did the musical I am Koryoin presented in 2020. In addition, it is essential to unfold diverse initiatives to raise awareness about Korean expatriates. Events such as the Koryo-saram history talk held in Pyeongtaek City in 2023 can be a model example. Moreover, recalling their history is crucial for the Koryo-saram to shape their ethnic identity. The OKA should therefore augment the provision of school supplies and scholarships to overseas Korean schools in order to incentivize students to remain connected to their Korean roots. The Uzbek Koryo-saram Odintsova Yuliya acknowledged in an interview with SKT, “In Uzbekistan, we have more than three Korean universities, educational centers, and youth centers,” referring to the successful interactions that must be implemented in other countries.

-Welcoming the Future

To aid the settlement of Koryo-saram in Korea, the government should spare no effort in enhancing its capabilities. Essentially, special Korean classes must be established to help their social integration. In particular, Weekend Schools must be instituted for laborers with weekday shifts, and language proficiency test preparation classes should be provided as a foundation to meet the requirements for permanent residency. For adolescents, bilingual teachers should hold supplementary Korean classes. Additionally, the Koryo-saram’s legal status must be amended to anchor their lives in South Korea. Just as the fourth generation of Koryo-saram were eventually recognized as overseas Koreans after legal revisions in 2019, amendments related to visas should be added to ensure stable residency regardless of the country from which they may come. Furthermore, the government should stipulate laws such that the families of Koryo-saram can also take up residence with equal rights and occupation entitlements. Jecheon City is implementing a region-specific visa program for Koryo-saram who are relocating to areas with declining populations. The program provides legal assistance to ease residency requirements and allows the employment of non-Korean spouses. By implementing these methods more broadly, Koryo-saram may finally feel a sense of belonging after so many years of being lost away from their roots.

In 1937, the Koryo-saram were compelled to board trains with unknown destinations, leaving everything behind. Despite the trials and tribulations, they refused to give up, instead striving to adapt to the different languages, cultures, and societies they faced. Nevertheless, their history has been neglected for a long time. The SKT hopes society will move beyond confining the compatriots under the frame of outsiders and instead search for ways to construct an integrated society.