Every year, Korean students entering Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU) compete fiercely to get admitted, as many Kingos did. This gateway for higher education has become a social issue as competition increases yearly, especially in the capital area. As students flock to Seoul City for better conditions, non-metropolitan universities are left empty. Before this disparity becomes irreversible, join the Sungkyun Times (SKT) to uncover the structural issues concerning domestic universities.

Korean Education at Crossroads

-High Pressure for College Admissions

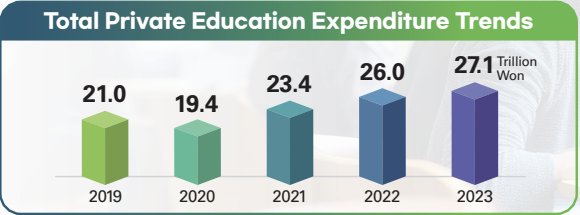

Fierce competition for admission is a major social issue addressed in South Korea every year. As for SKKU, the 2025 early admissions closed with a competition rate of 35.92 to 1, demonstrating the extent of the competition. Amid this, students invest significant effort and expense to enter their desired universities, enrolling in supplementary private education beyond regular schooling to enhance their abilities. In fact, according to analyses by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS), private education expenditure totaled ₩27.1 trillion in 2023, breaking records for three consecutive years. While the private education market is increasing every year, the spending varies remarkably depending on the region of residence and the income level of each household.

According to the same data, in 2023, the average monthly private education expenditure per student was highest in Seoul City at ₩628,000, compared to the national average of ₩434,000. Furthermore, the average educational spending by region was highest in the order of metropolitan cities, small and medium-sized cities, and lowest in townships. As capital regions are usually equipped with better educational institutions and academies, the inequality in education opportunities between provinces intensifies even more. Consequently, the disparities in admission to top-tier universities based on areas of residence worsen. The competition becomes more concentrated inside Seoul City, and eventually, the universities inside and outside Seoul City become dichotomized.

-Growing Disparities between Regions

As many prestigious universities are clustered in Seoul, the competition to enter these top-tier universities in the metropolitan area, also known as so-called in-Seoul universities, is acute. The ardent desire to enter in-Seoul universities is attributed to the advantages of securing a job and the region’s well-established cultural, residential, and transportation infrastructure. Lim Hye-won, a junior at Pohang City’s Handong Global University, told the SKT, “It is difficult to transit in Pohang as there are no subways, and it is impossible to enjoy cultural activities,” expressing the challenges faced. As local talents move to Seoul in pursuit of better education and enhanced convenience, the agglomeration of the population accelerates. According to a 2024 analysis by the Future Education Policy Research Institute of the publisher U’s Line, 35% of the universities nationwide were in Seoul City, and more than 40% of all freshmen students were concentrated in those universities in 2023. However, while the enrollment rate of metropolitan universities is increasing, the provincial universities have been witnessing a decline. This phenomenon leads to universities’ financial difficulties, as insufficient demand prevents them from increasing either the quota or tuition, pushing them to the verge of closure. The National Assembly Budget Office reported in 2024 that the 17 general and junior universities that closed since 2000 were all located in non-metropolitan areas. As the decline of local universities accelerates the transfer of local talents, the educational imbalance between regions is an urgent issue that must be addressed before the vicious cycle deepens its roots. Various institutions are striving for solutions, yet their effectiveness is uncertain.

Solutions Meet Shortcomings

-Easing the Pressure: Regional Proportional Admission System

Last August, the Bank of Korea (BOK) released a report proposing the regional proportional admission system, in an attempt to address the social problem of overheated competition for college admissions. The suggested admission method consists of the universities, each with their criteria, distributing the admission quota reflecting the ratio of the school-age population by region. In the report, the BOK emphasized the need for proactive responses arguing that the fierce competition increases the burden of private education expenses and deepens the educational inequality. In particular, it criticized the college enrollment rates based on geographic locations that are not directly proportional to the student’s potential and asserted that society should break out of the bad equilibrium to provide equal opportunities for all students. However, while many people relate to the issues presented by the BOK, whether this system can be a fundamental solution is controversial. The greatest limitation of this policy is that the provincial brain drain bringing the “Lost-Einsteins” phenomenon can intensify the concentration in the capital region and further exacerbate regional disparities. This proposal focuses on easing the competition by expanding the in-Seoul admission opportunities for students nationwide, disregarding the alternative of improving regional universities. As a result, the efforts to disperse the competition that converged in the capital can backfire by fueling the competition for in-Seoul admissions in the regional areas.

-Revitalizing Regions: Glocal University 30 Project

To overcome the educational imbalance and the local towns’ extinction crisis, the MOE initiated the Glocal University 30 project in 2023, where 30 local universities would be selected sequentially to be developed into leading global-level universities. This grant application project secures selected universities with funds of ₩100 billion distributed over five years, to cultivate competitive local universities through innovation and structural reforms. 10 universities were selected in 2023, including Hallym University in Chuncheon City, under the innovative model “Artificial Intelligence Education-Based Creative Talent Development University.” However, despite the benevolent intent of revitalizing local universities and their regions, there are criticisms that it could aggravate the gap not only between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, but also among universities within non-metropolitan regions. This means that even if a selected university succeeds in the reform, this could lead to a hierarchization of universities, causing the unselected ones in the region to become marginalized. To illustrate this further, Gwangju Health University, which applied as a coalition, was selected as a Glocal University in 2024. Meanwhile, Chonnam National University in Gwangju City damaged its reputation when it was reported to have failed to be nominated for two consecutive years.

The Road Ahead for Higher Education

The prestigious universities’ reputations and high-quality education that favor conditions when looking for a job exacerbate the fierce competition and investment in private education even more. Therefore, providing internships or job opportunities will help regional universities to enhance freshman enrollment rates. For example, Shudo University, located in Hiroshima, Japan, has agreements with 20 local companies, organizations, and local governments, providing students with internships and collaborative research opportunities. By strengthening industry-university cooperation and promoting it for freshmen recruitment, regional universities in Korea can also expect an increase in application rates. This strategy would prevent the provincial brain drain and elevate the attractiveness of the universities. Nevertheless, relying solely on internal reforms is not enough to compete with universities in Seoul City, which offer better accessibility, infrastructure, and employment opportunities. Instead, improvements in the surrounding environment must be made to be more appealing to students. Taking the example of the reference model for the Glocal University initiative, Malmö, the port city in Sweden initially based on manufacturing industries, became a startup innovation hub through efforts to revitalize the region. Its government made an urban reform that converted the place into a convenient, eco-friendly city and established the Malmö University and startup promotion policies to attract young students.

There has also been a case within South Korea where the relocation of governmental or national institutes in Sejong City resulted in a significant population influx as infrastructure such as children’s centers, sports facilities, and libraries were established. Likewise, by ameliorating facilities around university areas to ensure that students can secure stable jobs and enjoy convenience, local cities will be able to attract the young population. Eventually, for a region or university to be attractive to young students, investments in accessibility and infrastructure must be made. Ultimately, the government and universities need to understand what students want and respond accordingly, paving a smooth road toward the future of Korean universities.

Students simply make choices that are beneficial for their future. After that, problems that stem from these choices are tasks assigned to adults. While the government is making efforts to establish a balanced education environment, it is unclear whether achievements will be made. The SKT hopes Kingos, direct participants in the Korean education system, will also ponder the future of Korea’s fair and robust educational culture.